NIXONLAND: FRANKLINS vs. ORTHOGONIANS

By Rick Perlstein

Scribner, New York

2008

NIXON (to an aide): “It’s a piece of cake until you get to the top. You find you can’t stop playing the game the way you’ve always played it because it is part of you and you need it as much as an arm or a leg…. You continue to walk on the edge of the precipice because over the years you have become fascinated by how close to the edge you can walk without losing your balanceâ€

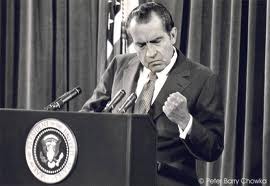

Rick Perlstein’s NIXONLAND dishes up the traditional Nixon, Tricky Dicky, one of the worst (at least until recently) presidents in American history. This is not Tom Wicker’s revisionist Nixon, this is Nixon in all of his noir glory, the master manipulator, the man who never told the truth if he could avoid it. It is a comfortable Nixon, the Nixon of my memory. And it is one difficult to reconcile with the revisionist Nixon, which is closer to Nixon in his own eyes. The revisionist says, “Sure, Nixon was a son of a bitch, a liar, a manipulator. So were Truman, Kennedy and Johnson, and Eisenhower for that matter. He just got caught.†I don’t think the revisionist Nixon is quite right, but it is provokative, and a necessary corrective to what has become a caricature of a complex, dark, enigmatic political figure whose successes, failures and motives are difficult to pick apart or even define. One thing is certain, he, along with Lyndon Johnson, shaped the post-war American political landscape perhaps more than anyone else. Race, the environment, poverty, welfare, health insurance, the use of the American military, and, especially, the limits of executive power, were dramatically defined either in reaction to these two men or by them. We are living with the consequences now.

This is Rick Perlstein’s thesis: That the Nixon years, and their relevance to our own time, can be analyzed as a conflict between, and exploitation of, the mutual fear, incomprehension and hatred of two groups in our country, the elite Franklins, and the ordinary Joes called Orthogonians.Â

While I find the thesis to be limited, Perlstein’s use of it is both entertaining and informative. He writes a cultural history of American internecine violence from 1964-1972 that is to the novelist and Nixon hater a delicious lunch. To the serious historian it no doubt appears to be a gross simplification. I am a novelist, not a historian. I was amused and disgusted and occasionally, discovered something I did not know. In these desperate times it is good to be reminded that Nixon, Reagan and Wallace actually were the bastards of my memory, not merely shrewd politicians with the guts and instincts to sense where the gutter of American politics was and go for it. Though they were of course that too.

The root story, the origin myth is this: when Nixon turned down his admission to Harvard (because his father would not pay the train fare, which happened to my uncle too) he matriculated at Whittier College. There he attempted to join an elite student society, The Franklins. He was turned down by them and rather than sulk in private, rather than become a campus shooter, or lonely alcoholic bum, he got even. He formed his own club, The Orthogonians (orthogon meaning right angle, Straight and Square), made up of the students rejected by the Franklins. This pattern, of both sharing and exploiting the feelings of rejection and hostility towards the elites of ordinary people, would be Nixon’s meat and potatoes for the rest of his career.

“Part of Nixon dreamed of world peace. Part of him gave the public something it wanted as much or more: an outlet for their hatreds….[W]hat Nixon saw as fighting evil and what much of the country saw as fighting evil overlapped. They identified with Richard Nixon—not despite the anxieties and dreads that drove him, but because of them.â€

And what did they hate 1969 and 1970? Here is his description of the final convention of the SDS:

“….One faction, the Progressive Labor Party, a severe, crew-cutted Maoist cell that banned the use of drugs, had stealthily taken over the SDS bureaucracy. Another faction…joined in tactical alliance with a group that called themselves The Weathermen to try to win the organization back. They labeled Progressive Labor false Maoists and ersatz revolutionaries and had attempted to prove their revolutionary superiority by recruiting angry white working-class high school students, who were supposed to serve as foot soldiers under the vanguard leadership of The Black Panther Party. The Weathermen were, meanwhile, working to harden themselves as urban guerilla warriors and had brought black and Latino street toughs into the meeting as ringers. When an entyirely separate faction, the Women’s Liberation caucus, offered a motion against male chauvinism, the street toughs roared back in mockery, chanting, ‘Pussy power! Pussy power!’ The floor disintegrated into a cacophony of contending chants: ‘Fight male chauvinism! Fight male chauvinism!’ “Read Mao! Read Mao! Read Mao!’â€

Although the book concentrates on the greatest hits of the period, there were incidents I knew about but had never read about in depth. His description of the Newark Riots is shocking, and forces the reader to remember that police violence in this country was routine and condoned, much worse than it is now, even given the well publicized abuses in major cities . For several pages he documents and describes each murder committed by the National Guardsmen, and state and local police. It is harrowing. These are the conditions that preceded the riot:

“The biggest city in New Jersey was a frighteningly corrupt town….Newark had the highest percentage of substandard housing of any American city: 7,097 units had no flush toilets; 28,795, no heaters. Twenty-eight babies died in a diarrhea epidemic in 1965, eighteen of them at city hospital, which was also infested by bats. The city’s major industry was illegal gambling. Cops ran heroin rings. Food stores raised prices the day welfare checks arrived.â€

The uprising began when rumors got out that a black cab driver had been killed while in police custody. The response was to protest, and then, when police surrounded protesters, to hurl names, followed by bricks and garbage. Soon looting and arson broke out. City officials didn’t respond, and the police, who felt handcuffed, took matters into their own hands:

“At eight thirty a father driving with his family to White Castle slowed for a barricade. Guardsmen opened fire. His ten-year-old son, Edie Moss, was mortally wounded in the head.â€

“At 6pm bullets ripped through the windows of Eloise Spellman, a forty-one-year-old widow, on the tenth floor of the Hayes Homes project. Her son and daughter watched her die. The shooters were guardsmen and state troopers, who reported she died of sniper fire.â€

“Rebecca Brown, thirty, liked to sit at her second-floor window. She kept a color photo of the Star-Spangled Banner clipped from the New York Sunday News on the wall. An adjacent wall was pocked with twenty-six automatic-weapons bullets from street level, one of which killed Mrs. Brown.â€

And so on. His finally entry is:

“One more corpse wasn’t included in the Newark death toll: a cop with a conscience who testified against his comrades during the grand jury investigation of the riot died of ‘occlusive coronary arteriosclerosis’ while ‘visiting friends at 25 Gold Street,’ a newspaper said. That address was the police clubhouse.â€

Altogether 26 people were killed and 1500 injured. 43 years later and Newark is still recovering from these events.

Perlstein doesn’t flinch from describing left wing violence in the same period, but he contextualizes it by reiterating the obvious, that left wing violence, and African American uprisings, were in response to something.

Perlstein throughout restates his thesis. In the chapter on the student takeover of Willard Straight Hall at Cornell University, after describing a surreal series of confrontations between the administration and radical, African American students, and the reaction of white jocks, he writes:

“What one side saw as liberation the other saw as apocalypse: and what the other saw as apocalypse, the first saw as liberation: Nixonland.â€

Nixon used this dichotomy to divide and conquer within his own party too. The Checkers Speech was meant to keep him on his party’s ticket, when Dewey and other Franklin Republicans were trying to get Ike to punt him. Nixon was only there as a sop to the paleo-conservatives and the virulent anti-communist right. Country club Republicans loathed this switchblade yielding ball-kicker from California. The Checkers Speech firmly cast Nixon as a victim, of the press, of the rich and the sophisticated. Moreover, what he was accused of doing was not only legal, but the opposition, the ultimate Franklin Adlai Stevenson, had done it too. Telegrams in support of Nixon ran something like 100,000 to one and Eisenhower had no choice but to retain him. It was one of the many ‘soiling humiliations’ Nixon would transcend and yet, in a most Hegelian way, retain the shadow of for the rest of his career.

In our perpetual amnesia we seem to forget that the rhetoric used during say, the recent health care debate was identical to that used in the early sixties, by many of the same people, who opposed civil rights legislation of any kind on constitutional grounds. Here’s Perlstein on George Wallace in 1966, commenting on increased federal efforts to gain southern compliance with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which denied federal money to any institution that discriminates:Â

“There were twenty-two senators from states of the Old Confederacy. Eighteen of them signed a letter to the president calling [revised federal schooling guidelines] an ‘unfair and unrealistic abuse of bureaucratic power.’ George Wallace….read a joint statement standing beside the Alabama congressional delegation that the guidelines were an ‘illegal’ and ‘totalitarian’ ‘blueprint devised by socialists.’ His school superintendent observed that Section 256 of the state constitution—‘Separate schools shall be provided for white and colored children, and no child of either race shall be permitted to attend a school of the other race’—forbade the state from compliance. Wallace went on statewide TV to announce that HEW had ‘the unqualified, one hundred percent support of the Communist Party, USA, as well as all its fronts, affiliates and publications.’â€Â       Â

The election of 1968 was a squeaker. Despite a severe lack of funds, a party divided against itself and widespread disgust Humphrey almost made it. Was it because half the nation or more wanted out of Vietnam and didn’t really believe Nixon had a secret plan? Perhaps. That would appear from the record to be the issue that gave Humphrey the bump he needed, as he moved away from Johnson in October of 1968. Race on the other hand was not just dividing the country but was slowly, as the Civil Rights Acts of 1964, 1965 and 1966 encroached on white privilege in the north, pitting the ‘silent majority’ of white working class Americans against a liberal minority, identified now with radical youth, black revolutionaries and intellectuals. Nixon paid close attention to the election of 1964, when Goldwater got the nomination through grassroots organizing and took the south from Democrats. Wallace and Reagan were quick studies in the art of exploiting the hatred and alienation of white, blue collar people, the traditional Democratic base, but Nixon was the master. He used buzzwords and innuendo where Wallace and Reagan engaged in overt racism and red-baiting. It was exploitation of this as yet narrow niche, and the promise to end the war in Vietnam, that got Nixon into the White House. What unfolded over the next 5 1/2 years of his presidency was the continued heightening of this division and the policies the strategy served. It was also the violent beginnings of what we now know as the culture wars.

Nixon’s policies are hard to assess. What to Wicker is an accomplished and somewhat invisible domestic record of continued liberal government, enforcement (eventually) of Supreme Court desegregation orders, the EPA, etc. is to Perlstein actually more subterfuge. Nixon, when faced with legislation he did not like, often undermined it. The NEA is a case in point. Nixon hated the NEA, hated northeastern artists and intellectuals, hated the city elite that the NEA served. But rather than doing the conservative thing of abolishing it, he actually increased funding, something liberals could hardly refuse. But he put the funds in the form of state grants and thus screwed big city arts organizations. His means then were hard ball politics. Where he was subtle and crafty in the world of policy, he was criminal, blatant and paranoid in his pursuit of reelection, which came to consume all that he did. What developed out of all this was an assertion of executive power that eventually brought him down. But in this he was continuing an evolution that began much earlier in the century, albeit to serve ends other than reelection.

Lyndon Johnson abused executive power, but he did so with a guilty conscience. He hid what he was doing, he lied, because as a man who had served most of his career in the legislature, as a congressional aide, congressman and senator, and the ultimate retail politician, he knew the executive had to have legislative support. Where he could not get it, as with Vietnam, he lied. And he covered up the lies. He also knew that wiretapping was illegal. He lied about it. Â

Kennedy’s arrest of steel executives at midnight, use of wiretaps, and tacit approval of the assassination of the Ngo brothers, Johnson’s Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and the entire conduct of the Vietnam War, are but a taste of what would come under Nixon. Nixon, without consultation, waged war on two sovereign nations (Laos and Cambodia), and took the US off the gold standard and imposed Wage and Price controls without any congressional consultation. His diplomatic negotiations with China and the Soviet Union were conducted in secret. He blackmailed corporations into contributing to his campaign. He had the IRS, FBI and CIA investigate and harass his political opponents. This kind of exercise of executive power is unthinkable now, even given Cheney and Bush’s abuses. Moreover, the Bush/Cheney abuse of executive power was, on the part of Cheney, an explicit effort to return to Nixon’s doctrine of The Imperial President, a president who was above the law. It was Reagan appointees who then took this ad hoc assertion and justification for unlimited executive power and crafted the constitutional theory of the strong executive. That argument was used to justify W’s abuses. In this sense then the Bush abuses were laid out by Nixon and Reagan as a permanent option for right wing governance in America. Â

Tom Wicker’s biography of Nixon, One of Us is much more sympathetic and famously shifts attention from foreign to domestic policy as the place of Nixon’s accomplishments. Perlstein has none of this. But Perlstein’s main point is not to crucify Nixon but rather to connect him directly to the politics of today. If there is less violence than in the early seventies, we are certainly living in what he calls Nixonland, and it is a terrible and unintended legacy. Nixon and Johnson before him destroyed the faith Americans had in their government because they were shown to be corrupt liars. Yet both men honestly believed that their political machinations, and their venal pursuit of money, were in the service of something, that government exists to solve problems. It was Reagan who didn’t just pay lip service to anti-government conservative rhetoric. He took American disillusionment with corrupt government and used it to destroy the idea of government itself. We have lived with this absurd nightmare ever since. And somehow the violence, fury, paranoia and activism of the Right are no longer countered by the Left. The Left has been in the position of defending government instead of challenging it. It’s only appeal is to reason, and as we know from Julius Caesar, given a choice between the reason of Brutus and the will of Caesar, the people will run Brutus out of town on a rail, leaving their ears to Antony.

I believe that Nixon had genuine abilities, both as an executive and as a man, but the record of abuses so undermines the accomplishments that it is hopeless to try to separate them out. He saw much. If he ramped up inflation for cynical political reasons, fearing recession more, he also looked at the balance of trade and concluded that America would no longer be the sole economic power in the world. Perlstein brings this point out and it is a good one, because Nixon’s solution was to lie about to the American public, and it was part of his motivation in taking us off of the gold standard. He saw that in order to retain military power we would have to have relations with China. He saw this in the early sixties and played a close hand. Not even Kissinger knew what he planned. If he knew Vietnam was unwinnable it did not stop him from prolonging the war for his own purposes, and he was sadistic in his use of bombing. Even compared to W’s use of torture, and the deaths in the civil war in Iraq, Nixon’s policies in Vietnam were criminal. Under Nixon and Johnson there were millions of Vietnamese killed, hundreds of thousands held as political prisoners in the south, and CIA and South Vietnamese police torture was widespread, common, and far worse than anything done at Gitmo or Abu Ghraib. But in the sixties these actions fueled American disgust and opposition to the war, caused our loss of faith in the government. It brought down two powerful and popular presidents. By Reagan’s time only a minority cared, and under Bush/Cheney there were no consequences whatsoever.

Nixon was partly a creature of his times, of history, and he was certainly justified in feeling bitter that he got caught at playing a nasty game others had played against him. In The Nixon Presidency: an Oral History of the Era (Deborah Hart Strober and Gerald Strober eds., Brassey’s, Washington DC, 2003) McGovern is quoted as saying no one could believe that Nixon would keep the tapes. He could have just burned them. Nixon’s hubris was such that he really believed the tapes were his, and his obsession with history, with his own image, was such that he couldn’t give them up, they were his guarantee of being able to write the triumphant story of his administration. Nixon wanted the final word on his presidency. Perlstein often refers to his ‘soiling humiliations’, invoking the trope of shitting ones pants, of being pelted with fecal matter. This is the low Nixon. The Nixon riding in a motorcade in Venezuela, defiant of the mob throwing rocks and garbage at him. I don’t think it should blind even the Nixon hater to the complex truth of this man. Perlstein’s book then lays out the idea that Nixon was no worse than we are. He knew us better than we knew ourselves, and we are living, every day, with his dark legacy.

Well researched. Breezy yet detailed. You are an underground scholar.

Coming from a Man of Letters I take that as a great compliment. thank you.