The Four Zoas of American Poetry

A causal reader of this blogh might conclude that I am an anti-intellectual when it comes to poetry. While I think any of my poems or prose or these posts would show that I am not in the least bit anti-intellectual, but rather anti-academic, it is true that I believe poetry to be a product of the imagination, not the intellect, and that I hold these two faculties of the mind to be distinct. Reason and intellect play an important role in any kind of writing. I am not an artistic anarchist to the extant that I think anyone can write poetry. I do reject any notion of objective standards or outside authority, but that merely puts the burden of a theory, standards and authority on the shoulders of the individual artist. No art is possible without measure. But that measure must be part of the personal revelation and expression of each artist, working both within and against their tradition or, more likely, traditions. Each great poet realigns the canon. The canon, the real canon of working artists, not the academic one, is an expression of each generation’s judgment of the art that precedes it. And, of course, there is the context of ones times, towards which I anyway feel an unending antagonism. As I grow as an artist it seems my task is to understand that antagonism as opposed to just riding it for all it’s worth. However, it is only given to a person to understand so much. Too much understanding destroys creativity.

Â

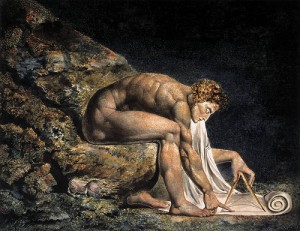

An idea which has been in my head for quite some time is that of the Four Zoas of American Poetry. The major schools of American poetry, its divisions, correspond to Blake’s Four Zoas. The Zoas are: Urizen (Reason), Luvah (Emotion), Urthona (Imagination), and Tharmas (Instinct).

Â

Poetry that is merely emotional or instinctual is boring and self-indulgent, usually formless, but possessed of drive and energy. Its primary quality is that of sound, the rush of spoken language. Much of Beat poetry (not, and this is important, the best of it) and definitely the majority of performance and slam poetry is like this. The integrity of the emotion, the rawness of the instinct, hungry and horny, are the defining qualities of this writing. The method is irrational free association. It is anti-intellectual, anti-tradition, anti-craft. But it is also the indispensable beat, the undercurrent of raw emotion and instinct which gives all great poetry its power. Luvah, emotion, becomes Orc, the fiery prophet of revolution in Blake’s mythology, who is bound and crucified by Urizen, the insane rationalist. Orc easily mutates into his opposite, The Law Giver, as did Moses and Christ.

Â

Urizenic poetry yokes together two opposed camps, the POMO experimental scene that emerges from LangPo and their enemy, the New Formalists. Both camps are the Bolsheviks of the poetry world. Their poetics are exclusionary, and they see the poem as a constructed product serving a definite purpose. The formalists subject the rhythmic thump, the funk of watery Tharmas and the rage of burning Orc to the iron bounds of regular rhyme and meter, and insist that this is the necessary constraint of civilization on feeling, without which we would be plunged into chaos and anarchy. Their appeal is always to reason and tradition. The academic avant-garde on the other hand rejects reason and tradition and sees the task of the artist to be ikonoclastic. Unlike the poets of Orc their revolution is philosophical. They are especially suspicious of any appeal to emotion or instinct as an instance of fascism. Myth, the archetypes, appeals to the soul are manipulative. Their ikonoclasm, like the religious version, rejects the image as false and derives, ultimately, from the post modern interpretation of Saussure, a rejection of the referentiality of language. The great beast of their world is the remarkably beautiful word phallologocularcentrism. Their poetry cannot be understood apart from a complex philosophical, political aesthetic that seeks to instantiate in each syllable their skepticism. Their appeal is to the mind, to ones judgment about the world.

Â

Urthona is the Zoa of imaginative poetry. The imagination is the creative faculty that integrates all of the others. It is our point of contact with Aeternity. Surrealism and the Deep Image folks are imaginative poets. If Tharmas and Luvah are the primal rhythm of poetry, the heart beat, Urthona works in punctuated images. It is the soul’s experience of the world expressed in a succession of pictures or metaphors. Purely imaginative poets like Ashbury lack feeling and thought. One only has the language of shifting images, representations, collages of sounds, thoughts and visions delivered in a mundane voice. Stevens and Crane on the other hand are imaginative poets who draw from the other wells. Frank O’Hara is another. Bob Dylan. Jack Gilbert. We don’t live in an age bereft of poetry, we live in an age divided against itself. That is the story that The Four Zoas tells.