Moldy Preachers

On False Naivete

Not long ago i sent my curmudgeonly friend Philip a Kimya Dawson song I like, and he sent back a curmudgeonly reply, to the effect that he loathes Kimya Dawson and all of her ilk because he loathes false naiveté. I do still love the song I sent (Underground) but find his analysis to be indisputable. Kimya Dawson, in The Moldy Peaches and as a solo performer, is responding to the endemic, or epidemic, irony, cynicism, nihilism and faux sophistication of her older contemporaries with raw, earnest, literal, naive expressionism. Taken too far it is sappy, sentimental and as false as the things she’s rebelling against. My friend Philip also bemoans the rapidity with which things in the arts are co-opted and commercialized. He points out that it took many years for the East Village to go from a genuine bohemia to a totally Disney fake bohemia, while the same process occurred in Williamsburg in a relatively brief period of time. Good things die almost before they are born. Kimya Dawson is a typical Williamburg product. Or Portland, Oregon. Or wherever. But this leaves open the question of, where do you go? How do you counter faux cynicism without embracing faux naiveté? How the hell do you even know what to do or think when every road appears to be not just marked off but cut off? If playing until your fingers bleed is a cliché, and so is its opposite, then paralysis sets in and nothing gets done at all.

I am thinking about this both in my own life and when I consider a poet I like quite a bit, Dorothea Lasky. I saw Dorothea read. She was great, invigorating, funny, direct, explosive and in love with words, with the rush of words and feelings. She was in love with emotion, that most despised word in art. Nearly all serious poetry holds emotion in contempt. It equates feeling with cliché and sentimentality. Not Dorothea. But I feel far more analytical when it comes to poets as opposed to pop singers. And what my friend says of Kimya Dawson I sense in Dorothea, and it is alarming. Dorothea it seems to me writes too much, and is too in love with her own sense of emotion. The things i find liberating and beautiful in her poems can easily turn into false naiveté. I have Black Life in my hands, her new book. Dorothea is an east coast poet, from Philadelphia. She has a lot of fans. She is riding the crest of a wave that is opposed to post-lang po and lang po sophistication, with its crossword puzzle word games, minimalism, intellectualism, abstraction and conceptualism. She isn’t going to write poems based on the first three letters of every fifth car she sees. She isn’t out to transform consciousness through ironic self-awareness of ideological linguistic structures. She isn’t out to destabilize anything. She isn’t locked in an agon with a tradition that hasn’t existed for a hundred years. But she is not a boring old ‘School Of Quietude’ bird watcher either. Her birds are nasty pigeons. She writes on the fly, the way Frank O’Hara did, but unlike O’Hara she seems to pretend she doesn’t know things that she does. Frank O’Hara wasn’t naive about anything. He just delighted in being a jaded old queen at night and virgin in the morning.

The Legend of Good John Henry

When my dad got Alzheimer’s all the plants died

In the nursing home there are no plants

There is nothing to live for

Dogs circle the pink painted building

The orderly staff waits with the bleach

Asking me where the diapers are

As I flip through this book I find all of the things I love about her poetry, but I also sense that it has become mannered. I go back to Awe (which is not in my office, as I write, so I can’t quote it) and see how when I first read her, heard her, I felt the flame of Blake running through her work, a wayward, religious light she was unembarrassed of, and which guided her on her hijinks. It is full of humor, self-mocking, to be sure, and unsettling, but still, I knew she wasn’t joking when she talked about God. I am not a religious person, I am an atheist, but I am tired of knee-jerk atheism. It bores me. It renders the world incomplete. It is not sophisticated or intelligent. Lasky seemed to be saying, ‘I’ve read Charles Bernstein and Ron Silliman and Louis Zukofsky and I understand and I don’t care, this doesn’t speak to me, their world is not my world.’ And I was thrilled, because this is how I feel. And this is how poetry works. You search and search for a poet who thinks and feels as you do. Or I do. Anyway.

Then I read something like this poem, from Black Life:

EVER READ A BOOK CALLED AWE?

Have you ever read a book called Awe?

I have. I wrote it. That’s my book.

I wrote that book. I wrote that one.

Some people read it. they said,

We will makle your book.

I said, Really? I love you.

They said, We love you, too.

I said, Good then

I will love you forever.

They said, Great! And looked scared.

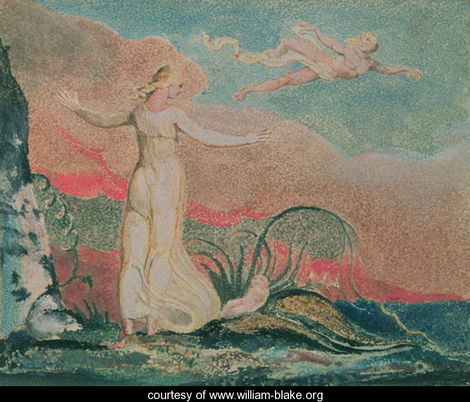

It isn’t right to judge a book by its worst poem, but I think Dr. Johnson said something along the lines that your contemporaries will judge you by your worst work, and posterity by your best. Or something like that. Poems like this are a waste of my time. They remind me of Kimya Dawson’s song about her mother dying. It starts out hauntingly, but by the second chorus she’s talking about Bert and Ernie and Mr. Hooper. She’s writing like a child. It’s not childlike in the sense that Matisse and Picasso were after, a shedding of sophistication a search for spontaneous and simple beauty rooted in design and color. It is childish in the sense of Blake’s Thel, of innocence as a refusal to be adult, to work through to the other side. Dawson confronts her mother’s death and runs to childhood, which is exactly what Thel does in The Book of Thel. Thel runs around essentially asking of all things, ‘Are you my mother?’ as in the child’s book. She gets to a worm, a cloud and a clod of dirt. They all assure her that they will die. Then the tone of the poem changes from innocent pastoral a harrowing invocation of the pit:

The eternal gates’ terrific porter lifted the northern bar:

Thel enter’d in & saw the secrets of the land unknown.

She saw the couches of the dead, & where the fibrous roots

Of every heart on earth infixes deep its restless twists:

A land of sorrows & of tears where never smile was seen.

It is interesting that in Black Life there is a strong current of sexuality, of sex, of boy friends, ex husbands and men that is not in Awe, and that loss of sexual innocence is also the underlying loss in Thel, that sexual innocence and death are linked, there as here, in this case her father’s illness and (I suppose) death. It is the refusal of knowledge of sex and of death that condemns Thel to an eternal childhood, a senility that is sterile and frightening, the sterility of one who refuses to become conscious and live. A clinging to childishness in the face of cynicism is the same move. To go against artistic sophistication doesn’t mean refusal to BE.

THAT ONE WAS THE ODDEST ONE

That Robbie Wood is so weird

He seriously makes me want to fuckl his brains out

Oh fuckable man, why do you have to do and say such

Strange things?

I LOVE A MATHEMATICIAN

I love a mathematician

Not a man who lives by himself in a minivan, which one is he?

Masturbating to my picture on the internet, just like the fat one in the basement

Masturbating and masturbating, oh how I love that

And would love to drain the blood from his face too

In personÂ

O how I would identify with the sickly nature of love

And sweet sticky kisses

That never go away.

I want to travel with Dorothea through all of this. But poem after poem in this book, wherever I turn, there is this false note of childishness.

The Animal

My heart belongs to a lion

I love his pelt and covet his heart

O animal, your heart is wise beyond your years

I cut your paw and tell you in a whisper

To never leave this place

I want Dorothea to write like she writes, in the end. I don’t doubt her sincerity. And it is a struggle to get from art to sincerity without losing the art. She has decided to be herself, a modernist and a romantic who is unafraid of unadorned feeling, and simple statement. But preciosity is as much a problem as the tone deaf minimalist philosophizing of so much serious poetry. I love Oppen but there are times when his ear utterly fails him, as it does Creeley, as it does Delillo in prose, and Pynchon, and David Foster Wallace. Yet time and again i read their ears praised, that they have a great ear for the language. If they do then you have to have a great ear for them.

Lasky isn’t afraid of the old art of poetry. She isn’t afraid of gushing. But I think she writes too much. This is Blake’s The Book of Thel :

The Book of Thel

THEL’S MOTTO

Does the Eagle know what is in the pit?

Or wilt thou go ask the Mole?

Can Wisdom be put in a silver rod?

Or Love in a golden bowl?

I

The daughters of Mne Seraphim led round their sunny flocks,

All but the youngest; she in paleness sought the secret air,

To fade away like morning beauty from her mortal day;

Down by the river of Adona her soft voice is heard,

And thus her gentle lamentation falls like morning dew:

“O life of this our spring! why fades the lotus of the water?

Why fade these children of the spring, born but to smile & fall?

Ah! Thel is like a watry bow, and like a parting cloud,

Like a reflection in a glass, like shadows in the water,

Like dreams of infants, like a smile upon an infant’s face,

Like the dove’s voice, like transient day, like music in the air.

Ah! gentle may I lay me down, and gentle rest my head,

And gentle sleep the sleep of death, and gentle hear the voice

Of him that walketh in the garden in the evening time.”

The Lily of the valley, breathing in the humble grass

Answer’d the lovely maid and said: “I am a watry weed,

And I am very small, and love to dwell in lowly vales;

So weak, the gilded butterfly scarce perches on my head;

Yet I am visited from heaven, and he that smiles on all

Walks in the valley and each morn over me spreads his hand,

Saying: ‘Rejoice, thou humble grass, thou new-born lily flower,

Thou gentle maid of silent valleys and of modest brooks;

For thou shalt be clothed in light, and fed with morning manna,

Till summer’s heat melts thee beside the fountains and the springs

To flourish in eternal vales.’ Then why should Thel complain?

Why should the mistress of the vales of Har utter a sigh?”

She ceasd and smild in tears, then sat down in her silver shrine.

Thel answered: “O thou little virgin of the peaceful valley,

Giving to those that cannot crave, the voiceless, the o’ertired;

Thy breath doth nourish the innocent lamb, he smells thy milky garments,

He crops thy flowers, while thou sittest smiling in his face,

Wiping his mild and meekin mouth from all contagious taints.

Thy wine doth purify the golden honey; thy perfume,

Which thou dost scatter on every little blade of grass that springs,

Revives the milked cow, & tames the fire-breathing steed.

But Thel is like a faint cloud kindled at the rising sun:

I vanish from my pearly throne, and who shall find my place?”

“Queen of the vales,” the Lily answered, “ask the tender cloud,

And it shall tell thee why it glitters in the morning sky,

And why it scatters its bright beauty thro’ the humid air.

Descend, O little cloud, & hover before the eyes of Thel.”

The Cloud descended, and the Lily bowd her modest head,

And went to mind her numerous charge among the verdant grass.

II

“O little Cloud,” the virgin said, “I charge thee tell to me,

Why thou complainest not when in one hour thou fade away:

Then we shall seek thee but not find; ah, Thel is like to Thee.

I pass away, yet I complain, and no one hears my voice.”

The Cloud then shew’d his golden head & his bright form emerg’d,

Hovering and glittering on the air before the face of Thel.

“O virgin, know’st thou not our steeds drink of the golden springs

Where Luvah doth renew his horses? Look’st thou on my youth,

And fearest thou because I vanish and am seen no more,

Nothing remains? O maid, I tell thee, when I pass away,

It is to tenfold life, to love, to peace, and raptures holy:

Unseen descending, weigh my light wings upon balmy flowers,

And court the fair eyed dew, to take me to her shining tent:

The weeping virgin trembling kneels before the risen sun,

Till we arise link’d in a golden band, and never part,

But walk united, bearing food to all our tender flowers.”

“Dost thou O little Cloud? I fear that I am not like thee;

For I walk through the vales of Har and smell the sweetest flowers,

But I feed not the little flowers; I hear the warbling birds,

But I feed not the warbling birds; they fly and seek their food;

But Thel delights in these no more, because I fade away,

And all shall say, ‘Without a use this shining woman liv’d,

Or did she only live to be at death the food of worms?'”

The Cloud reclind upon his airy throne and answer’d thus:

“Then if thou art the food of worms, O virgin of the skies,

How great thy use, how great thy blessing! Every thing that lives

Lives not alone, nor for itself; fear not, and I will call

The weak worm from its lowly bed, and thou shalt hear its voice.

Come forth, worm of the silent valley, to thy pensive queen.”

The helpless worm arose, and sat upon the Lily’s leaf,

And the bright Cloud saild on, to find his partner in the vale.

III

Then Thel astonish’d view’d the Worm upon its dewy bed.

“Art thou a Worm? Image of weakness, art thou but a Worm?

I see thee like an infant wrapped in the Lily’s leaf;

Ah, weep not, little voice, thou can’st not speak, but thou can’st weep.

Is this a Worm? I see thee lay helpless & naked, weeping,

And none to answer, none to cherish thee with mother’s smiles.”

The Clod of Clay heard the Worm’s voice, & raisd her pitying head;

She bow’d over the weeping infant, and her life exhal’d

In milky fondness; then on Thel she fix’d her humble eyes.

“O beauty of the vales of Har! we live not for ourselves;

Thou seest me the meanest thing, and so I am indeed;

My bosom of itself is cold, and of itself is dark,

But he that loves the lowly, pours his oil upon my head,

And kisses me, and binds his nuptial bands around my breast,

And says: ‘Thou mother of my children, I have loved thee

And I have given thee a crown that none can take away.’

But how this is, sweet maid, I know not, and I cannot know;

I ponder, and I cannot ponder; yet I live and love.”

The daughter of beauty wip’d her pitying tears with her white veil,

And said: “Alas! I knew not this, and therefore did I weep.

That God would love a Worm, I knew, and punish the evil foot

That, wilful, bruis’d its helpless form; but that he cherish’d it

With milk and oil I never knew; and therefore did I weep,

And I complaind in the mild air, because I fade away,

And lay me down in thy cold bed, and leave my shining lot.”

“Queen of the vales,” the matron Clay answered, “I heard thy sighs,

And all thy moans flew o’er my roof, but I have call’d them down.

Wilt thou, O Queen, enter my house? ’tis given thee to enter

And to return: fear nothing, enter with thy virgin feet.”

IV

The eternal gates’ terrific porter lifted the northern bar:

Thel enter’d in & saw the secrets of the land unknown.

She saw the couches of the dead, & where the fibrous roots

Of every heart on earth infixes deep its restless twists:

A land of sorrows & of tears where never smile was seen.

She wanderd in the land of clouds thro’ valleys dark, listning

Dolours & lamentations; waiting oft beside a dewy grave,

She stood in silence, listning to the voices of the ground,

Till to her own grave plot she came, & there she sat down,

And heard this voice of sorrow breathed from the hollow pit:

“Why cannot the Ear be closed to its own destruction?

Or the glistning Eye to the poison of a smile?

Why are Eyelids stord with arrows ready drawn,

Where a thousand fighting men in ambush lie?

Or an Eye of gifts & graces, show’ring fruits and coined gold?

Why a Tongue impress’d with honey from every wind?

Why an Ear, a whirlpool fierce to draw creations in?

Why a Nostril wide inhaling terror, trembling, and affright?

Why a tender curb upon the youthful burning boy?

Why a little curtain of flesh on the bed of our desire?”

The Virgin started from her seat, & with a shriek

Fled back unhinderd till she came into the vales of Har.