may sinclair

Recently I stumbled on the English author May Sinclair (1863-1946) in the back pages of Dorothy Richardson’s Pilgrimage. My copy of Pilgrimage is published by Virago, so it makes sense that Sinclair would be there. She was a major feminist writer and thinker and active in modernist circles. She supported herself as a writer from 1896 on, and in 1918 reviewed the first three books of the multi-volume Pilgrimage for the Egoist. She was the first to apply the term stream of consciousness to a literary text and soon after used the method herself in fiction. She was interested in mental health reform and studied psychoanalysis and wrote a book of Idealist philosophy. Her study of the Brontes influenced her to write two volumes of weird/ghost tales (still in print in various forms).

The Bronte book is interesting because it is part of an evolving feminist lineage of the English novel. In fact it is impossible to construct a canon of English fiction without women authors, who have produced major and transformative works of fiction every step of the way from the 16th century to today. The first book by a woman novelist about a woman novelist was Gaskel’s biography of Charlotte Bronte. That it is a hit job against Bronte’s father and husband and grossly mischaracterizes life in the Bronte household is beside the point, I think.

In 1914 she went to Belgium with an ambulance corps to care for wounded Belgian soldiers, a brief but intense and traumatic experience she wrote about in a number of poems. She wrote other important reviews in the Egoist and the Little review, about H.D., Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot, all of whom she knew, as well as Ford Maddox Ford. Her list of works is very long.

I have been interested in women novelists for a long time now, so coming across her added to what is already a mighty stack of books. I will probably read her supernatural tales and two of her novels, The Life and Death of Harriett Frean and Mary Olivier: A Life.

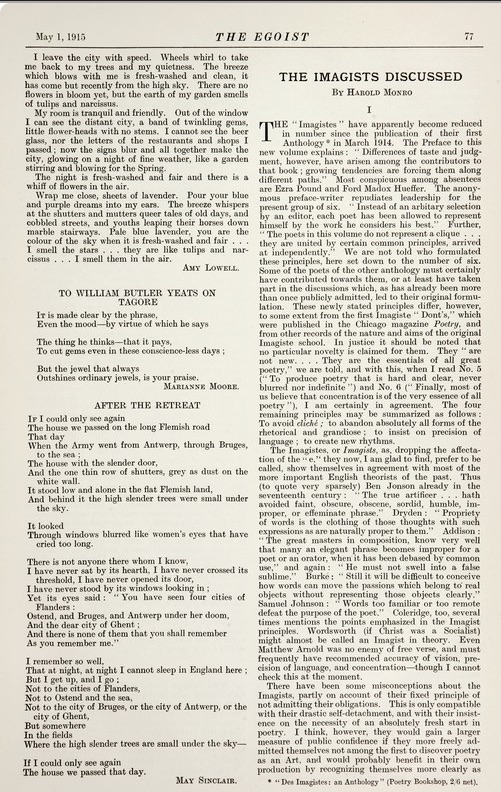

I am writing this now because last night, noodling around, I found one of her poems about WWI, and it is a stunner. Versions on blogs and the poetry websites seemed to be off in the lineation, so I tracked down the original version in the Egoist (1914) and copied it out from there. The lineation on other sites was fine. One of the features of the poem is an alternation of extremely long lines with extremely short ones, which presents problems in any format.

AFTER THE RETREAT by May Sinclair (1863-1946)

If I could only see again

The house we passed on the long Flemish road

That day

When the army went from Antwerp, through Bruges, to the sea;

The house with the slender door,

And the one thin row of shutters, grey as dust on the white wall.

I stood low and alone in the flat Flemish land,

And behind it the high slender trees were small under the sky.

It looked

Through windows blurred like women’s eyes that have cried too long.

There is not anyone there whom I know,

I have never sat by its hearth, I have never crossed its

threshold, I have never opened its door,

I have never stood by its windows looking in;

Yet its eyes said: “You have seen four cities of Flanders:

Ostend, and Bruges, and Antwerp under her doom,

And the dear city of Ghent;

And there is none of them that you shall remember as you remember me.â€

I remember so well,

That at night, at night I cannot sleep in England here;

But I get up, and I go:

Not to the city of Flanders,

Not to Ostend and the sea,

Not to the city of Bruge, or the city of Antwerp, or the city of Ghent,

But somewhere

In the fields

Where the high slender trees are small under the sky—

If I could only see again

The house we passed that day.

This is I think a beautiful poem and the more I read it the sadder, more tragic it becomes. By the fourth or fifth time I felt tears in my eyes. Perhaps it is the time we live in. The poem speaks to the emotional devastation of war. America at the moment feels like a country in the depths of war. As of this writing, October 27, 2020, right before the election that will decide our fate, 220,000 Americans have died in less than a year. The last time we experienced a plague of this proportion was 1918, the year Sinclair reviewed Pilgrimage.

There is a gentleness to the cadences and a slightly old fashioned, 1890s feel, like Yeats’ Lake Isle of Innisfree, with its long languorous lines. But it is closer to prose and hasn’t his formal regularity. This a modernist poem influenced by Imagism. Pound, under the influence of Ford, was pushing for prose-like clarity in poetry, in the hard images and affectless sonics of In the Station of the Metro. If you look at the page of the Egoist on which this poem appears, there is the end of a group of prose poems by Amy Lowell; an article, The Imagists Discussed by Harold Munro; and a poem by Marianne Moore called To William Butler Yeats On Tagore. Prose enters English poetry through the Imagists, by way of the French. French poetry is syllabic, and amenable to prose rhythms in a way that English poetry, heavily stressed, is not. Both Blake and Whitman wrote long lines of seemingly proselike poetry, but their cadences are heavily stressed and have not the quality of the prose poem as it evolved in France and among English Modernists like Ford, Pound, Eliot and Moore. And of these Marianne Moore wrote in syllabics. Her line could be quite long and I don’t think of her writing as the blank verse (unrhymed iambic pentameter), of Marlowe, Shakespeare, Milton, Stevens and Eliot. Moore’s The Black Earth was published in the same April, 2018 issue of the Egoist as May’s review of Pilgrimage.

Sinclair’s use of adjectives is striking. Slender, thin, low, and small are repeated. They do not have the sentimental feel of diminutives. When used to describe trees it reminds me of Mondrian’s tree paintings from the teens, natural form becoming abstract. Her use of place names is incantatory, as if they were living entities. Her grief is palpable in the objective details (and the descriptions are photographic, strongly objectivist) but it is the house with the slender door and one thin line of shutters that won’t let her go. Personifying the house seemingly makes her an old-fashioned poet indeed. Ruskin condemned this as the ‘pathetic fallacy’ in 1856. It is one of the opening salvos against 18th and 19th century sentimentalism in poetic theory. In 1919 Eliot came to the rescue with the ‘objective correlative’. The objective correlative is a dramatic, outward representation of the deep and impersonal emotional complex of a work, a symbol not an allegory. The house:

“It looked/

Through windows blurred like women’s eyes that have cried too long.â€

There is nothing sentimental about this line, it is a truth of war and this poem represents the war through a woman’s eyes and through a strong woman’s ‘I’ repeated throughout. The house addresses her as a lover claiming she will not remember the other places she has been to. And it is true. In the penultimate stanza, back in England, she cannot sleep. She gets up and must go back in memory to the field where that house stood. She longs to return. Is this not the feeling of every traumatized soldier who longs to return to war? War will not let her go. It has captured her unconscious mind. All of her life’s passions are gathered here in this poem, psychoanalysis (theory of trauma), paranormal experience (haunted by a house), objective modernist description and aesthetics, and most of all, the centrality of women’s experience.

Weaver, Harriet Shaw (editor)

London: The New Freewoman, Ltd., 1915-05-01 20 p.; 31.5 x 21 cm

Damn Perfect

thank you, keith!