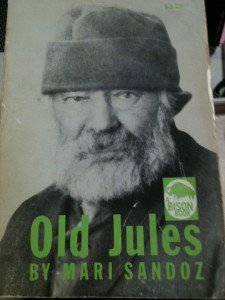

MARI SANDOZ & OLD JULES

By Mari Sandoz (1896-1966)

“Spring came to the range country with the swiftness of the swallows. In the morning snowdrifts lay deep along the wagon trails. In the evening the low valleys gleamed with lakes of rose and orange reflecting the delicate sky. In a few days translucent grasses pushed through the shallower reaches, misting the blue with green. Wild ducks darkened the open water and quacked and quarreled as they fed along the shores. In the swamps the hell-divers chattered and mud hens fought or led their early hatching out for swims, a dozen wine-colored plush birdlings bobbing along behind the black mother hen.â€

Old Jules is a biography of an American pioneer, written by his daughter Mari and published in 1937. Mari Sandoz is an extraordinary figure in American letters and this, her first book, is a great book. I want to say it is one of the greatest books written about the American west, but I haven’t read that many so I won’t make the claim. I will say it is one of the greatest books I’ve read about a place.

“At the potash towns the old plants loomed gaunt, fire-stripped, the boilers and pipings red-rusted, the large chimneys tumbled down to piles of brick. The tar-paper shacks were gone, the towns dead. On all sides the hills pushed in.â€

The place is the Sand Hills of Nebraska and the time is from the 1880-1928, the year in which Old Jules dies. The sweep is epic, as it should be, but the prose is the thing. Sandoz achieves several things seemingly without effort. She describes the sights, the smells, the attitude of place, of nature, people and the ephemeral things the people build against a relentlessly fickle environment, an environment hostile to permanence. She tells and retells stories she heard as a child, about the ordinary adventures of humans caught in a drama only partly of their making, a drama driven by greed and dreams and contradictory impulses: rapes, murders, suicides, corruption, yes; but also work, fencing, planting orchards, selecting ground, establishing institutions such as post offices, courts and police; and marriage, divorce, madness, adultery; the making of clothes, shoes, buildings, and the forging of weapons and tools; and the celebrations, weddings, funerals and Sunday dinners and dances of life on the frontier. History happens meanwhile, the indigenous Cheyenne and Sioux come and go, the wild game disappears, the railroad and towns arrive, the land is no longer free and then automobiles and telephones and finally radio and airplanes. Sandoz is a master of narrative and of language, for she captures the speech rhythms and phrases of her settlers, almost all of whom are immigrants: Polish, German, French or like her father, Swiss. Sandoz didn’t speak English until she went to school, against Old Jules’ wishes, at the age of 8. She lived in a linguistic environment that was French and German and, likely (according to Sandoz scholar, Richard Voorhees), Cheyenne and Sioux. Time passes as effortlessly as a gentle stream in this book. Change is its theme, and yet change happens, time passes, in the organic, elemental way of life, sometimes eruptive, explosive but mostly at the pace of erosion.

Old Jules was born in Switzerland in the 1850s to a bourgeois family. When his father tries to clip his wings the impulsive Jules quits medical school and takes off for America. He ends up as a freeholder in the panhandle of Nebraska. Here his obsessions unfold. Jules is a violent, abusive, paranoid and angry man with a tyrannical will for dominance. He marries 4 times, driving one wife insane. He rarely bathes, shoots a gun with deadly accuracy, and lives in filth, among books he orders from the government and abroad. He fights with everyone and whips and beats his children and wife Mary. He is a torrent, a walking storm. His dream, his obsession, is to settle the land which he has loved since first seeing it. He is a prophet. He knows good weather will succeed drought. He knows mild winters will punctuate the thankless freezing blizzards of the worst years. He develops seeds and plants that are draught tolerant (he is known by the end as the Burbank of the upper Plains). He will do anything to attract settlers, and is joined by his brothers, and his wife’s family, seduced to the harsh land by Jules’ charm and vision. By the turn of the century he is a legend, but his restless, reckless pursuit of sensation doesn’t desert him until near the end when he begins to drink and take morphine for chronic pain. By then his family seems to have forgiven him. I say seems because there is a current of anger that runs through this book that perhaps is his greatest gift to his daughter Mari. She does not in any way idealize this man, she simply presents him as a force few can resist or hide from. When she wins a short story contest in the late twenties he sends her a letter saying, “You know I consider artists and writers the maggots of society.â€

Sandoz herself had a remarkable career as a writer. Old Jules went to something like 70 publishers before it was accepted and became a hit. She was suspected throughout her life of plagiarism, and she struggled with editors and agents often, changing both frequently. The publishers were in the east, and they wanted to change her language to make it more accessible and conventional, which she resisted fiercely and with much bitterness. As a result she decided to move to NYC in the 1940s (she wrote a marvelous piece about her first apartment there) and essentially spent the rest of her life traveling between archives in the west and in New York, and living in Nebraska where she interviewed, and archived, the genealogy and lives of people. I mentioned Richard Voorhees earlier. I met Voorhees in connection with research I’m doing on Marianne Hauser, who was Sandoz’s friend. Voorhees was much involved with The Mari Sandoz Heritage Society, and visited Sandoz’s sister in Nebraska. He has seen the archive of material Sandoz kept, with her Native American friends relating stories going back 6, 7, 8 generations. Her research was massive and detailed and her files run to many thousands and thousands of pages. She drew on this to write a series of histories and historical novels about the west. Old Jules is but one of what is known as the Trans Missouri Series, which includes a biography of Crazy Horse, a history of fur trappers called The Beaver Men, and Cheyenne Autumn. She also wrote a novel about her childhood called Slocum House.

Sandoz was a tough person. Her letters are strictly business. She was married when quite young but divorced her husband and scorned relationships. In a letter she wrote in the late fifties she says she loves avant-garde art and experimental fiction. She mentions Celine as a writer she admires. To call her a woman novelist would be insane, yet she suffered through the realities of being a woman in a man’s world. Self-pity did not exist in her make up. I want to end this with a few quotes, but also, I would urge anyone who loves the English language to plunge into this book and luxuriate in the reality she creates a word at a time.

This is Jules, dressed up to meet Emelia, one of his wives when she first arrives:

“An old man. Gray under the greasy cap; limping despite all he could do—a slouchy stooped, careless figure with burning eyes. Then she noticed the hands: long fine fingers, smooth, almost white. They showed no brutalization, not the hard lot of a peasant that his appearance suggested.â€

They arrive at his home at night:

“After supper, which they ate from the frying pan because there were no dishes, he showed his wife his guns, his traps, his stamp collection, his notary-public seal. She looked at them all, her hand never leaving her lap, and when she could she stole glances about the bare room, the floor of rough foot-wide boards with big cracks between, the homemade table with no cloth, the two windows staring blankly out into strange darkness, unrelieved by curtain or shade, the rusty stove with a brick for a fourth leg.â€

This is her description of her mother, Mary, in middle age:

“Mary had three anaemic, undernourished children very close together, without a doctor. She lost her teeth; her clear skin became leathery from field work; her eyes paled and sun –squinted; her hands knotted, the veins of her arms like slack clothesline.â€

A hail storm:

“Then suddenly the hail was upon them. A deafening pounding against the shingles and the side of the house, bouncing high from the ground in white sheets. One window after another crashed inward, the force of the wind blowing the blankets and sheets into the room, driving the hail in spurts across the floor, until white streaks reached clear across it. Water ran in streams across the wide cracks between the boards.â€

The defendant in a Murder trial:

“It was admitted that Nieman was wild, an unruly boy, a desperate youth. He had several knife scars, a bullet furrow or two. But his mother pleaded so eloquently for a new start for him, and her hair was white and waved and her cheeks beautiful, her dress soft, blue stuff. On the other side sat the widowed Helen, the passion of her dark eyes imprisoned in a body heavy with repeated child-bearing. Around her were seven sharp-featured, undernourished children. All of them were brown and wind-burned, their hands bony and calloused, their clothing old and patched, strange and frightened, the mother with no knowledge of English, no eloquence that the jury would know.â€

Jules on his deathbed:

“They took [Marie] to the hospital room where an old, old man lay, his face a thin gray shell of wax with a few straggling beard hairs like wire. His faded eyes opened. They slid over Marie without recognition and closed, but not quite. Behind the slits he watched that they did not leave him alone.

“The sight shook the eldest daughter. From such a being, helpless, without personality, without fire, a man had grown as from a tiny cloud a storm spreads, to flash and thunder and roar and bring rain to the needy earth, in the end to disintegrate, to drift in a pale shred of non-descript cloud.â€