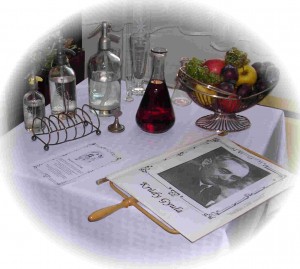

GYULA KRUDY: SUNFLOWER

GYULA KRUDY: SUNFLOWER

SUNFLOWER is a novel of deep nostalgia, written in 1918 by the great Hungarian novelist, journalist and storyteller Gyula Krudy. Set in the Magyar homeland, it narrates in long meandering dreamlike passages a year in the life of its heroine, Eveline. Eveline lives in a divided world, that of cosmopolitan Budapest and the country estate she has inherited. The novel begins when her would-be lover Kalman, a city rake, robs money from her bedroom while she sleeps and escapes through the garden. It is an intensely erotic scene, and eroticism suffuses every syllable of this book. Gyula is obsessed with women, with women’s bodies, with the smell of women, and he is obsessed with language. The two are intertwined with the Hungarian countryside such that each appears to be the reflection of the other and the three sinuously wind their way through the readers mind.

Eveline decides to remain at her country estate and not return to the city. She is in love with two men, Kalman and a local aristocrat, a relative, Almos-Dreamer. Her friend from the city, Miss Maszkeradi, joins her. Miss Maszkeradi is a sarcastic, cynical young city woman who sleeps with whomever she pleases. But the binary invoked here is not that of virgin and whore so much as cosmopolitan and country aristocrat. This is Eveline’s dilemma, whether to remain on the land of her ancestors, with Almos-Dreamer, or the city, with Kalman and Maszkeradi. There follows not a story so much as a series of imaginary and pastoral flights of surreal language invoking the erotic life of this vanishing province. (After World War 1, when this book was written, Hungary would be dismembered, and this division, this amputation, would fuel Hungarian politics through the coming decades, into the holocaust). A local reprobate, Pistoli Falstaff, attempts to seduce Maszkeradi, and falls in love with Eveline. The novel follows Pistoli for a long while, and narrates the genealogy of Eveline and Almos-Dreamer. It descends into bardo consciousness. The sentences pulse along, drifting like pollen on a breeze.

SUNFLOWER is of course decadent and perverse. Here is a Mr. Burman, one of the many lovers of Eveline’s great eponymous ancestor:

Mr. Burman never, not once, let on what an awful lot he knew about the clandestine amulets on necklaces concealed under women’s garments. For his afternoon naps at home his head reposed on a silken cushion stuffed with female hair, curls that women bestow only on especially favored lovers; he had also collected in his apartment such mementos, such as ladies’ shoes, forgotten petticoats, unforgettable hosiery, shifts, handkerchiefs, and hat feathers….

Krudy was born in the region where the novel is set, Nyiregyhaza. He lived in Budapest, where, like Pistoli, he was a compulsive drinker, womanizer and gambler. But his imagination is engaged by the home of his childhood, not the city that provided him with his livelihood. He is compared to Joseph Roth, but other than both being gamblers and drunks, they seem to me to have little in common. Both invoke Central Europe before The Fall, both are subject to nostalgia and sentimentality, but the world of Joseph Roth is harder, and the narration one of inevitable decline without solution. Krudy simply suspends time and enters the past through a vivid, sexual imagination. His drunkards are not the weak dissolution of a complicated but true aristocratic tradition; they are rather the symbol of that world’s vigour and refusal to knuckle under to hypocrisy. The violence and arbitrariness of that world are not so much ignored as seen at a distance, for his perspective is always that of the seducer or the seduced, and the love triangle, the adulterous affair, the seduction of a young maid by a decrepit, freebooting liar, the cuckolding of old men, and the acquiescence of old men to gout, decay and cuckoldry are is his subject, as well as the changing seasons. It reminds me other hermetic worlds, Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha, of course, but also Georges Bernanos’ hellish world of peasants in Mouchette. Mouchette is a tragedy and its heroine a martyr. The sexual current of her life is rape, lies, cruelty and abuse. Yet Bernanos’ also imagines an elementary pastoral setting, while hewing to the harrowing facts of Mouchette’s world of despair, a world without mercy or love. Another hermetic, sexual pastoral, Rikki Ducornet’s The Stain, more surreal, seems to take place in contiguous territory. I am also reminded of Pedro Paramo, by Juan Rulfo, for Nyiregyhaza is also at times a land of the dead. Ghosts and memories drift freely in and out of the minds of the characters. But the novel is devoid of Rulfo’s politics. Sunflower, unlike these other books, is a comedy.