The Vermillion Bird

Â

T’ANG IMAGES OF THE SOUTH

Â

By Edward H. Schafer

Â

University of California Press

Berkely and Los Angeles, California

Cambridge University Press

London, England

Copyright, 1967 by

The Regents of the University of California

Â

Â

INTRODUCTION

Â

“Although we know that high cultures were possible long ago in the dry hot lands of Egypt and Mesopotamia—partly because so many well-preserved museum specimens have been found there—we temperate-zone men have not been disposed to regard the moist tropics as conducive to the best flowering of human talent. This prejudice is now being abandoned. The rain forest and monsoon shores have, in fact, produced better things than enervation, laziness, lechery, and dullness of intellect. Indeed a thousand years ago many of the great centers of civilization were situated in tropical Asia and America, and we have discovered that we can admire the achievements of the Mayans, the Javanese, the Cambodians, the Singhalese, and many other people who flourished in the wet forests many centuries before the European Renaissance. Of course the dark men of the rain-soaked cities were not the only great sources of spiritual and material energy in the Middle Ages. Leaving Europe aside, there was also Islam, in its Persian, Arabian, Syrian, African, and Spanish varieties, in mainly arid lands. Finally, there was China, providing a mixed environment, ranging from beech and spruce forests, sandy deserts, and grassy steppes, through a temperate and subtropical lake country, and beyond that to a loosely held colonial frontier where the tropics begin. This last region is the subject of this book. In particular, I propose to examine its contributions to the knowledge of the medieval Chinese, and also its effects of their senses, sensibilities, and imaginations—or considered contrariwise, the transformation of this land by the alchemy of the Chinese spirit.â€

Â

This seems as good a way as any of starting the reading section of The Vietnam Project. Anyone interested in the early history of Vietnam will have to study the history of China. Part of this is because Vietnam was colonized by China. Famously, for nearly a thousand years, the Vietnamese people were either nominally or actually ruled by men of the north, the Hua men. (And we are for the most part talking about men, though Vietnamese history is full of important heroines and female warriors, the Britomarts of Nam-Viet, such as the Trung Sisters). Sometimes this meant that they paid tribute to the Chinese court, and at others it was ruled directly as an administrative province. For this reason Vietnam enters history through the brushes of Chinese Literati and bureaucrats. Geographical, historical, botanical, zoological, and anthropological information lie in the encyclopaedias and histories of China, as well as the poetry of exiles. As such, the information is not always accurate, and often fantastic. Vietnam was probably to China what Britain was to the Romans. And like Roman Britain, there arose a ruling class in Vietnam that was creole in nature, either nativized Chinese or Vietnamese administrators and warlords with Chinese habits and tastes. They came to adopt the biases and manners of their rulers, though this is a story for a different post, perhaps on Keith Taylor’s Early Vietnam. This post is devoted to The Vermillion Bird, and medieval China.

I said in an earlier post that this part of the world had inspired some of the greatest historical writing I have read. There are many marvelous stylists to be found in works of academic scholarship. Among the princes of this group is Edward Shafer.

Schafer’s book is a book for poets. He is as immersed in the English literary tradition as he is in T’ang exoticism. In the epigraphs to each chapter he quotes Blake, Coleridge, Swinburne, Browning, Stevens and Shakespeare. His vocabulary is as lush as his subject and he delights in words like peri (this is from Wikipedia: “In Persian mythology, peris (Persian: پری Pari) are descended from fallen angels who have been denied paradise until they have done penance. In earlier sources they are described as agents of evil; later, they are benevolent. They are exquisite, winged, fairy-like creatures ranking between angels and evil spirits. They sometimes visit the realm of mortals.â€), a word I came across coincidently in Keats’ Lamia. Here is a taste of his prose style, from late in the book. After translating scores of Chinese verses, Schafer here writes his own poem of the south:

“In T’ang times, a sensitive and observant visitor from the north could not have overlooked such wonders in the monsoon forest of Nam-Viet. It was a spangled world of bright birds, totally unlike the northern crow land, hawk land, sparrow land. To borrow the style of the fu, it was a world of

Â

Fierce lustrous drongos,

Fluttering scarlet minivets,

Skulking polychrome pittas

Darting iridescent bee-eaters—

Â

Fire-breasted flowerpeckers,

Fork-tailed sunbirds—

Â

Verditer flycatchers,

Paradise flycatchers—

Â

Babblers and bulbuls,

Trogons and tragopans.

Â

To say nothing of drongo shrikes, tailor birds, fantail warblers, babbling thrushes, white-eyes, Java sparrows, weavers and barbets—a world to seduce the imagination to feverish dreams.â€

Â

ITS BEGINNINGS ARE UNKNOWN

Â

Of Canton’s origins he writes:

Â

“Although set in a distant frontier region, where most settlements were recent, this was an old town. Its beginnings are unknown, but an old tradition told that its original site in Nan-Hai township had been marked off by five Taoist transcendents, who came down from the sky riding on multi colored goats and holding beautiful stalks of millet in their hands. Consequently the popular name for the city was ‘Walled City of the Five Goats’.

“In the eighth century, Canton had a population of about 200,000. It was a cosmopolitan city with a huge merchant class, chiefly Indochinese, Indonesian, Indian, Singhalese, Persian, and Arab….â€

Â

Shun is one of Goat City’s divine Heroes:

Â

“In another story Shun is pictured as a great deity in the Taoist style. He appears in the sky, with heavenly music, the shine of unearthly light, and the odor of divine perfumes, and accompanied by a host of heavenly beings mounted on fabulous beasts. He himself wears a jeweled hat and a cloak of feathers, and is girded with a sword. This magnificent apparition is for the benefit of a female adept engaged in yoga ascetic practices by the mountain sanctuary. The god delivers a long homily on the frailty and frivolity of secular life and an account of the subterranean geography of Mount Chiu-I, with its hidden mineral palaces guarded by poisonous reptiles and every kind of ferocious animal, and tells of the nine rivers which issue from it, with names like ‘Water of the Silver Flower’ and ‘Water of Eternal Security’. Impressed by her sincerity, Shun gives the maiden his personal instruction with the result that ten years later she ascends to heaven in broad daylight.

“Still, despite the special reverence given this antediluvian paragon, some of the captains and kings of the heroic times of Han loomed almost as large among the respectable gods of Nam-Viet. High among them was the King of Viet, the formidable Chao T’o….His voice could still be heard through the mouths of mediums….A fine tale of late T’ang times tells of a visit of a young man to his tomb, transformed into a Taoist grotto. Here it is in synopsis:

“The time is the end of the eighth century. Ts’ui Wei, a well-to-do youth of Canton spends his inheritance. He helps and old woman. She gives him some potent mugwart, with which he heals a strange man who, ungratefully, decides to sacrifice the young man to a familiar demon. He is rescued by the stranger’s daughter, flees into the forest, and falls into a pit where he heals a boil on the lip of a serpent-dragon. The happy dragon carries him deep into the bowels of the rock, where they find a splendid palace. Here he is faced with four riddles: 1. its unnamed prince is absent at a banquet with the god Chu Jung; 2. a lady named T’ien is introduced as his destined bride; 3. he is given a ‘national treasure, the Solar Igniting Orb’; 4. he is sent home riding on a white goat with the ‘Emissary of Goat City’. All of this is mysterious repayment by the lord of the underground palace for a service done him by our hero’s remote ancestor. In Canton, he learns he has been missing for three years! He sells the orb to a foreigner in the Persian Bazaar, who tells him that he has surely been in the tomb of Chao T’o, King of Nam-Viet, since the jewel, a treasure from Arabia, had been buried with him. Later, the young man sees the effigy of the emissary with the figures of five goats at the temple of the god of the city wall and mote—he was, of course, the protector god of Goat City, that is, of Canton….â€

Â

ANIMALS

He begins chapter 11 with a quote from Swinburne’s Hymn to Proserpine:

Where beyond the extreme sea wall, and between

the remote sea gates,

Waste water washes, and tall ships founder, and

deep death waits;

and then proceeds to Invertebrates, of which he has to say:

Â

“Our zoological view of Nam-Viet, because of the special interests of medieval observers, the relative abundance of animal species, and the chance survival of texts, will necessarily be incomplete. All kinds of creatures will appear intermingled, without systematic separation into faunal zones or biomes. Goat antelopes will hobnob with gibbons, as if modern ecology did not exist. We shall start off low on the evolutionary ladder, with a hodge-podge of spineless animals.

Â

In wilderness of gorges, poisonous birds come pecking after the boat;

By the blackness of caverns, vindictive snakes come

flying from the trees.

Â

So wrote Chang Pion on the fortunate return of a friend from the perilous confines of Annam. Envenomed wildfowl and winged serpents were part of the expected furniture of the monsoon forest. Even more zoologically plausible poems which tell of animal life of the Nam-Viet are turbulent with wild elephants, thunder-breeding dragoons, monster sea turtles blowing up waves, and prodigious clams glowing in their subaqueous lairs. Indeed even sober prose accounts tend to emphasize reptiles and slimy invertebrates—all of the hideous and demoniac crawlers of the sodden soils and heated seas of Nam Viet….

Â

Â

“We begin with a marine coelenterate, a jelly fish of Nam-Viet which the men of T’ang called tse…,or sometimes ‘sea mirror’, or, most often, ‘water mother’ [!]. This was a medusa, probably an Aurelia, of such tenuous substance that it was regarded as ‘basically a creature formed by the congealing of dark (yin) water’. The human inhabitants did not disdain to eat these humid animals, properly cooked and flavored with alpinia (‘wild ginger’), cardamoms, cassia and fagara. Their repute among the Hua men, however, was chiefly based on the observation that little shrimp swam along under their soft canopies, acting (it was thought) as eyes to warn of danger. This remarkable symbiosis provided a useful and hardly avoidable moral—a large but insensitive organism might profit from the help of lesser but more alert creatures….

Â

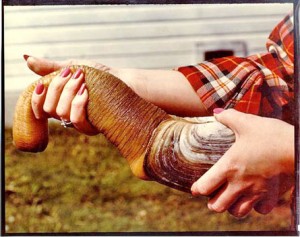

“Moving up the evolutionary ladder to the successful mollusks, we must begin with the most magnificent before attending to the more believable. The mysterious ch’en (zhin), akin to the treasure-hoarding sea dragons, but usually imagined as a gaping, pearl-producing, monster bivalve, was perhaps realized in the form of one of the giant clams of the tropical seas, Chama or Tridacna. A well-known creature of fantasy, it may have haunted the dreams of the pearl dealers, whose daily preoccupation was with their smaller relatives, particularly the pearl oysters of the offshore beds just west of the Lei-chou peninsula. The oyster pearls were much appreciated in the north, but one writer complained that the delicate flesh of their close cousins, much appreciated by the people of Nam-Viet, was ignored by the men of the north. The southerners boiled them, removed their shells, and ate them with pleasure. They were particularly enjoyed when taken with a cup of wine, and (contrariwise) the Lu-t’ing people of the water margin brought them impaled on skewers to exchange for wine in the public markets. This kind of edible oyster is called mou-li—the first syllable of its name written with the character for ‘bull; male animal’. But Tuan Ch’eng-shih was careful to point out that the Mou vocable’s masculinity was purely adventitious, and that the oyster was in fact a concretion, without benefit of sex, from saline water….â€Â Â

Â

Schafer’s books are still in print, or rather, back in print. Here is a link to the publisher:

Â

http://www.floatingworldeditions.com/books/vermilion-bird.html

Â

His other books are put out by them too, and you can find them on the website.

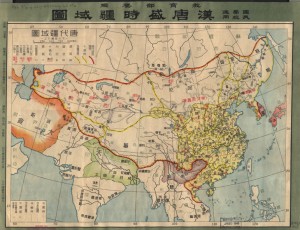

Much of the area he is talking about is considered part of China today. Only the very remote reaches of the region are actually part of modern Vietnam. Of course, modern Vietnam covers a much larger area of land than it did a thousand and more years ago. The Vietnamese were confined for centuries to the Red River Delta and environs (where modern day Hanoi is). Central Vietnam was Cham territory. The Cham are a tiny minority in Vietnam and Cambodia today, linguistically and culturally distinct from the Vietnamese. Southern Vietnam, the area around Saigon, and the entire Mekong Delta, were sparsely inhabited even into the 19th century. The ancient Kingdoms of Funan, Linyi, the trade entrepot Oc Eo, are all located here but little is known about them. Chinese Histories refer to them as kingdoms, but modern scholars doubt they were anything of the kind.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â