THE DOCTOR SPEAKS

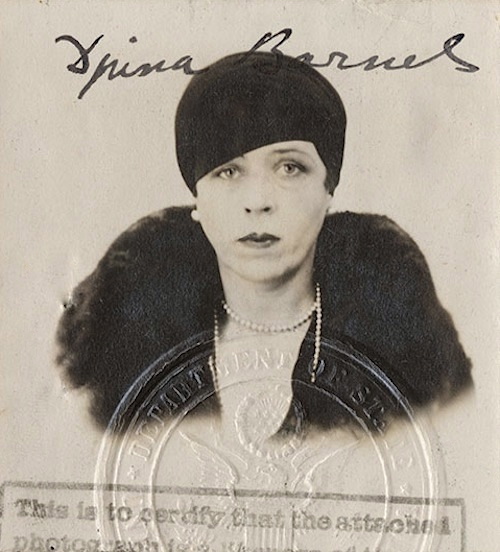

By Djuna Barnes

Nightwood, by Djuna Barnes, is one of the books I love best. I remember reading it at age 19 on the subway late at night. It was on the Columbia curriculum. I’m not sure if it was one of the ‘Great Books’ every freshman had to read (like Vico, ah, Vico, blessed Vico), but it was John Fousek, whom I followed to John Jay, as a non-matriculated, non-student in 1978, who gave it to me. I rode about Manhattan on the IRT disguised as a homeless drug addict reading Nightwood. Then, in my mid-twenties, I reread it, the thrill undiminished. I always intended to go back to Nightwood but did not until a few weeks ago. It has not lost its luster with age, no. The book is unlike any other. And it is striking that Nightwood is so singular, given that its roots are apparent on the first page. But this quality of singularity is shared by all of the great Modernist writers. Joyce, Lawrence, Barnes, Stein, Woolf, Lewis, Eliot, Pound, just are not alike.Â

Djuna Barnes’ voice is dense and decadent. It has not the cerebral range of Joyce, it is not grounded in the earth and labor as is Lawrence, and while satiric it is not quite as angry or angular as Lewis. Her modernism is not the modernism of the machine.  Repetition and impressionism are not its methods. Her imagery is vivid and organic. Much of the effect of her prose is achieved through extended description of characters and an Elizabethan use of simile and metaphor. There is also a epigrammatic quality to her writing which comes from Oscar Wilde and is unmistakable. To read a paragraph of Nightwood is to sit down to a meal of fois gras and Sauternes with an aging transvestite and an overgrown woman-child. The meal will be lit by church candles. And it will be in a Parisian garret, with Huysmans, Rimbaud and Baudelaire in attendance.

“Her trade—the trapeze—seemed to have preserved her. It gave her, in a way, a certain charm. Her legs had the specialized tension common to aerial workers; something of the bar was in her wrists, the tan bark in her walk, as if the air, by its very lightness, by its very non-resistance, were an almost insurmountable problem, making her body, though slight and compact, seem much heavier than that of women who stay on the ground. In her face was the tense expression of an organism surviving in an alien element. She seemed to have a skin that was the pattern of her costume: a bodice of lozenges, red and yellow, low in the back and ruffled over and under the arms, faded with the reek of her three-a-day control, red tights, laced boots—one somehow felt they ran through her as the design runs through hard holiday candies, and the bulge in the groin where she took the bar, one foot caught in the flex of the calf, was as solid, specialized and as polished as oak. The stuff of the tights was no longer a covering, it was herself; the span of the tightly stitched crotch was so much her own flesh that she was as unsexed as a doll. The needle that had made one the property of the child made the other the property of no man.â€

Nightwood begins with the birth of Felix. His mother dies in childbirth and his father, an Italian Jew living as an Austrian Baron, is already dead. Felix inherits the false title and a fawning attitude towards royalty, wealth and pomp. He craves acceptance. He is weak; a dilettante, a collector of things and people and the status that ever eludes him. He seems to embody a certain class of negative Jewish stereotypes. One of the truly difficult things about reading this novel is the apparent anti-Semitism of the first chapter. I have read enough academic papers asserting that the anti-Semitism is ironic so I accept this judgment. Nevertheless, for the Jewish reader the beginning is rough going, but then, for the lesbian reader I imagine the whole book is too. Nightwood is famously a foundational queer novel. But her lesbians are not heroic. They are insane, alcoholic and sex obsessed.

Felix falls in love with Robin, a tall, childlike drunk given to wandering. Robin is the central mystery of the story, the McGuffin its several characters pursue through nighttime Paris. She agrees to marry Felix, becoming a Baroness and bears his child, Guido. There is something wrong with Guido, never specified, but the implication is mental feebleness, a weakness of mind and character that goes beyond mental retardation and suggests rather genetic attenuation, the end of the line. Robin is never a captive of Felix. She deserts him nightly. He pursues her, follows her about as she drinks and picks up strangers. Eventually she leaves him for Nora, an American woman who is Barnes herself. Robin breaks Nora’s heart too rambling, drinking and disappearing. Robin, who is always observed, never observes, evidently cannot bear to be tied to a place or person.  Finally she deserts the beautiful and intelligent Nora for Jenny, a small, ugly, unpleasant woman determined to possess what others have. All of these doings are witnessed by and commented on by the magisterially sleazy, fallen, beautiful rag of a she-man, Doctor Matthew O’Connor. Much of the novel consists of his extended monologues, spoken to Felix and Nora, who come to him for spiritual advice and healing. He lives in filth and squalor. Barnes’ description of the good Doctor’s apartment, with its pots of makeup, suggests Swift’s Strephon poems. There is much in her prose style that hearkens back to 16th-18th century writing, when the language was more vigorous and the writers, and readers, less puritanical. Barnes is vulgar. She is rare in women writers of the time, perhaps singular, for her scatological obsessions. There are vivid descriptions of crotches, groins, of oozing genitals, of shit. A large penis is compared to a mortadella.

“A pile of medical books, and volumes of miscellaneous order, reached almost to the ceiling, water-stained and covered with dust. Just above them was a very small barred window, the only ventilation. On a maple dresser, certainly not of European make, lay a rusty pair of forceps, a broken scalpel, half a dozen odd instruments that she could not place, a catheter, some twenty perfume bottles, almost empty, pomades, creams, rouges, powder boxes and puffs. From the half-open drawers of this chiffonier hung laces, ribands, stockings, ladies’ underclothing and an abdominal brace, which gave the impression that the feminine finery had suffered venery. A swill-pale stood at the head of the bed, brimming with abominations. There was something appallingly degraded about the room, like the rooms in brothels, which gave even the most innocent a sensation of having been accomplice, yet this room was also muscular, a cross between a chamber a coucher and a boxer’s training camp. There is a certain belligerence in a room in which a woman has never set foot; every object seems to be battling its own compression—and there is a metallic odour, as of beaten iron in a smithy.â€

I have walked around with that passage in my head for 33 years, the final simile so captures the smell of a single man’s room. And I have been in rooms like this.

The Doctor’s monologues ramble, but not incoherently. He has the loquacity of a heavy drinker who does nothing but listen to gossip and confessions. His is the voice of Falstaff and of Lear’s fool. He adumbrates a philosophy of decadence and thrives on Wildean paradox. Like the French he is immersed both in Catholicism and heresy. When Nora comes to him to explain ‘the night’ he unleashes a staggering poem of nocturnal being, of people who walk the streets and are despised, who live for sensation without hope.

Barnes was writing about the lesbian demi-monde in Paris and Europe in the 20’s. Her eye and ear are acute. Her writing borders on satire but is firmly grotesque. The novel was published in 1936, and written in the early 30’s. The collapse of Europe into fascism and political violence lies just off the edge of the narrative. In 1991 a waitress I worked with, who was an AIDS activist, and a lesbian, told me she hated the gay culture of NYC in the 70’s because she said ‘we danced, while the right wing took over the country.’ What is seen in Nightwood is the dancing. The hellfire is not seen, but it must have been felt by readers at the time who could not have ignored the fact that Felix is an Austrian Jew.

Barnes had a bizarre upbringing in upstate New York. Her father and grandmother were advocates of free love and polygamy, and as a teenager she was married off to the middle aged brother of her father’s mistress. She fled with her mother and siblings to New York and began to write professionally, hanging out with disreputable bohemians in the Village. Her first published work was The Book of Repulsive Women, poems she published here and there that were oblique enough not to be censored for the evident (to the discerning eye) obscenity, including a rather juicy description of cunnilingus. Her poems are marvelous, and they all rhyme. Djuna Barnes wrote poetry for her entire life. The late poems are obscure to the point of incomprehensibility. But they grow from the roots of the earlier poems. From the start she is haunted by the death of a woman. Presumably this is the real life analog of the character Robin. In Barnes there is at work the cult of the body. The poems are witty, mean, and full of longing and grief. But these emotions are protected by a language dense with allusion and meaning, words that reach back hundreds of years to Malory and Marlowe, to Shakespeare and Donne. It is interesting that her poems do not suggest the French 19th century in the way Nightwood does. She also was a visual artist and illustrated Ryder (her first novel), and The Book of Repulsive Women. She was the last of the Modernist Lions to die, in New York, in the Village, a bitter, isolated, angry drunk. She was quite old and poor, but a hero for feminists, for lesbians, and for poets. Nightwood is short. It is easily one of the greatest novels ever written.

Thanks Jon,

Lovely! I’m off to our local library with Lily, to get it now!

–

You won’t regret it! And you’d love her illustrations.