The Psychopath Test for Novelists

In my review of Patrick Hamilton’s Hangover Square I asserted that the protagonist’s schizophrenia was a literary, not psychological diagnosis. I will admit to a certain flippancy in the comment, but I was disturbed by the diagnosis, it was not what my understanding of schizophrenia is. But it may have been close. The idea that a schizophrenic has multiple personalities went out the window with Sybil, at least and has found other windows to jump out of since. But poor old George Bone, while presented as having two personalities, can be seen as having a single personality subject to two states. That would indeed be closer to a both psychological diagnosis and the literary facts, his behaviour in the novel.

It brings up a vexed thing. I am now writing a book about people whose behaviour is clearly psychopathic. And yet I want my protagonists to feel love and guilt, two things we are assured psychopaths do not feel. Recently I listened to Jon Ronson’s The Psychopath test. It was hilarious and disturbing, yes, but even more disturbing to me because no matter how much he plays with the problem of psychiatric diagnosis, and suggests that psychopathology is a creature of a definition, he also makes a persuasive case for the reality of the personality type. So much so that Macbeth, as if we needed a psychiatrist to tell us so, is a textbook psychopath. He feels no remorse. He is a narcissist. He kills. He is hungry for power. His actions appear to himself to be inevitable. But what about Bonnie and Clyde? Are they psychopaths? Certainly. But the film can hardly suggest it because the film requires romantic outlaws. Noir anti-heroes like Walter Neff and Frank Chambers commit psychopathic acts but are not psychopathic. They have feelings of empathy. They are not crowing narcissistic con men but depressed, self-lacerating losers in love with women. My 500 year in the future LA noir required three bad people to get worse without being psychopaths. I didn’t want to write Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer on Mars. It is not going to be Hannibal Lector in the year 2525.Â

Nevertheless…I find myself eliminating feelings, insights, empathetic sensations from Bob Martin’s palette. Those colours don’t belong! I see-saw between the literary diagnosis, which is standard Noir, and a more realistic psychological angle. And it leaves me wondering if the literary profile of the killer even exists in the real world.

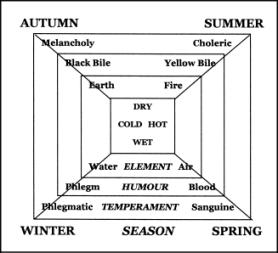

I can recognize Macbeth as a textbook psychopath, and Shakespeare, who is credited with creating modern psychology, even inventing the psyche modern psychology analyzes (I should not say psychology but rather psychoanalysis, a huge difference), actually believed in a humoural psychology. Even as he was exploring/creating the inner depths of the modern personality his theory was based on the Renaissance synthesis of Graeco-Roman philosophy and mysteries. It included in its grasp physiology, psychology, and cosmology. Alchemy is a branch, as is astrology. Robert Burton, Shakespeare’s near-contemporary (ten years separate their births) wrote the great psychological tome of this synthesis, the Anatomy of Melancholy. And Shakespeare himself was able to dramatize differing psychologies. Brutus is a Stoic who believes in fate, that character in some sense is destiny. But Edmund, a Machiavellian bastard, laughs at such notions. For him a man is sui generis. But then, this tells us nothing of what Shakespeare actually believed. Nevertheless, the prevailing, conventional theory of the time defined character types based on bodily humours: Choleric (yellow bile, hot and dry); Melancholic (black bile, dry and cold); Phlegmatic (phlegm, cold and wet); Sanguinary (blood, hot and wet), just as surely as today authors and others will tell you that the mind is made up of id, ego and super ego, that we project, introject and repress, and that there is a phenomenon known as transference and counter-transference..

Frank Norris and Emile Zola also believed that character was destiny, and their naturalism included the popular psychology preceded Freudianism. At the same time there was literary impressionism, the stream of consciousness of Henry James or Ford Maddox Ford’s accumulation of shifting, subjective details, which were more like a pointillistic account of the mind. This is closer to our own cognitive understanding.

I find modern psychologies disturbing perhaps because they are closer to the character as destiny view, as opposed to say, character as process. There is a Calvinist edge to the idea that we inherit mental illnesses like schizophrenia and psychopathology. Schizophrenia is believed to be highly treatable whereas psychopatholgy is a throw-away-the-key illness. Yet we do believe a psychopath can be made, if not un-made.

A question: aren’t all killers psychopathic, it is just the context that changes? Does the lone contract killer actually exist, a man in total control? Joey, of Joey the Hit Man, tries to convince us it is so, but Joey is a total psychopath. He only kills for money, sure, but he feels nothing. He abides by a code, but he has little impulse control. He understands order, and order maintained by violence, but in other areas, like gambling, he is out of control. He’s the real Tony Soprano, another lovable, redeemable (almost) sociopath.

Classical tragedy, as defined by Aristotle, has this Calvinist aspect. A plot is supposed to unfold like a trap. To the extent that character and plot mirror each other, there really can’t be another outcome once the thing gets going. The big bang of plot sets the parameters. It will end in death. Death is the mother of narrative! Death creates all that precedes it.

Still, going back to Shakespeare, it is easy to see that Iago is psychopathic, purely so, and a jolly, fun character because he has the actual hero as a foil. The play is about Othello and how a man like Iago can drive a good man to destroy the one thing he loves. Much is made of his motivation, but to me Iago’s motivation is clear: he was passed over for promotion. Edmund is also a jolly psychopath. One committed psychopath can do a lot of damage, but he doesn’t bring down the kingdom, Lear does. Lear creates the context where a monster like Edmund can thrive.

I will keep my characters true to literary life. I do need and want a psychological theory behind what I do, but I’m embarrassed by Freudian and Jungian understandings at this point. I suppose my real belief about the mind and how it works is pitched somewhere in-between traditional psychoanalysis (which appeals to my romantic, literary side, and is after all a scientistic continuation of traditional arcane mysticism) and contemporary cognitive/neurological/evolutionary understandings of the mind. Both seem to leave out something essential about human beings. The former is richer, because it includes in its portrait our portrait of ourselves, as accumulated in the wisdom traditions of the world. But things, as we know, can be very different from what they appear. That’s why we don’t have a Grand Unified Theory of mind yet.